Spelling

Why Correct Spelling Is Important

Correct spelling is still important. The National Commission on Writing for America’s Families, Schools, and Colleges (2005) reported that 80 percent of the time an employment application is doomed if it is poorly written or poorly spelled. Here are other examples of situations where spelling is important:

- Writing so others can read and understand

- Recognizing the right choice from the possibilities presented by a spell checker

- Looking up words in a dictionary

- Filing alphabetically

- Playing word games like Scrabble®

And even though word processing software includes spell checkers, students still need to become proficient spellers.

Spell Checkers Do Not Catch All Errors

Since the advent of word processing and spell checkers, some have argued that spelling instruction is no longer all that important. But spell checkers do not catch all errors. One study (Montgomery, Karlan, and Coutinho, 2001) reported that spell checkers usually catch just 30 to 80 percent of misspellings overall, partly because they miss homophone errors. A spell checker would find no errors in this sentence: “To miles is two far too go.”

Another problem is that students who are very poor spellers do not produce the close approximations of target words necessary for the spell checker to suggest the right word.

Spelling Is Important for Reading

Research has shown that learning to spell and learning to read rely on much of the same underlying knowledge—such as the relationships between letters and sounds—and, not surprisingly, that spelling instruction can be designed to help children better understand that key knowledge, resulting in better reading (Ehri, 2000).

Catherine Snow et al. (2005, p. 86) summarize the real importance of spelling for reading as follows: “Spelling and reading build and rely on the same mental representation of a word. Knowing the spelling of a word makes the representation of it sturdy and accessible for fluent reading.”

Spelling Is Important for Writing

Research also bears out a strong relationship between spelling and writing: Writers who must think too hard about how to spell use up valuable cognitive resources needed for higher level aspects of composition (Singer and Bashir, 2004). Writing is a mental juggling act that depends on using basic skills with automaticity (e.g., handwriting, spelling, grammar, and punctuation) so that the writer can focus on topic, organization, word choice, and audience needs. Poor spellers may restrict what they write to words they can spell, with inevitable loss of verbal power, or they may lose track of their thoughts when they get stuck trying to spell a word.

Spelling Needs to Be Explicitly Taught

The National Reading Panel Report (2000) did not include spelling as one of the five essential components of comprehensive literacy instruction. The report implied that phonemic awareness and phonics instruction had a positive effect on spelling in the primary grades and that spelling continues to develop in response to appropriate reading instruction.

However, more recent research challenged at least part of the National Reading Panel’s assumption. In a longitudinal study, Scientific Studies of Reading (2005), a group of researchers found that, although students’ growth in passage comprehension remained close to average from first through fourth grade, their spelling scores dropped dramatically by third grade and continued to decline in fourth grade (Mehta, Foorman, Branum-Martin, & Taylor, 2005). Clearly, we should not assume that progress in reading will necessarily result in progress in spelling.

Read Naturally programs for teaching spelling or that support spelling

Read Naturally programs for teaching spelling or that support spelling

Regular vs. Irregular Spelling Patterns

The spelling of words in English is more regular and pattern-based than commonly believed. About 50% of English words have regular spelling patterns. That means that the letters used to spell these words predictably represent their sound patterns. For example, the words bad, back, and bake all follow reliable, regular spelling patterns.

Another 37% have only one error if they are spelled on the basis of sound-symbol correspondences alone. Typically, that error would occur in spelling a vowel sound. The schwa sound is an example. If a student wants to spell the word temperature and knows that all vowels sometimes make the schwa sound (ə), that student knows that the sound alone will not help him to spell the word. The specific vowel needed for the third syllable in temperature must be learned in order to spell the word correctly.

The remaining 13% must be learned as irregular words (e.g., ocean), and many of these words could be spelled correctly if other information was taken into account, such as word meaning and word origin (Hanna, Hanna, Hodges, and Rudorf, 1966).

Spelling Strategies

How many words do we need to teach in our spelling instruction? The average person uses perhaps 10,000 words freely and can recognize another 30,000 to 40,000 words. Fortunately, to be an effective speller, a student does not have to be able to correctly spell all the words in his or her listening, reading, and speaking vocabulary. A basic spelling vocabulary of 2,800 to 3,000 well-selected words should form the core for spelling instruction (E. Horn, 1926; Fitzgerald, 1951; Rinsland, 1945; T. Horn & Otto 1954; Monson, 1975).

When choosing the words to include in spelling instruction, focus on regular spelling patterns, high-frequency words (both regular and irregular words), and frequently misspelled words.

Teaching Regular Spelling Patterns

Since 50% of the words children read and spell have regular spelling patterns (and another 37% are very close), it is smart to directly teach children the regular spelling patterns in our writing system. Students are introduced to sound/spelling patterns early through reading instruction, and then they study them again during spelling instruction.

Words with a regular spelling pattern should be taught using letter-sound correspondences—as sound-out words. Researchers found that the most successful approaches were based on structured spelling instruction that explicitly teaches speech sounds that are represented by the letters in printed words (Graham, 1999; Berninger et al., 2000; Swanson et al., 1999). The student identifies the individual sounds in a word and then chooses the correct letter (or letters) to represent each sound. Sometimes the sound is represented by more than one letter (e.g., sh).

Research shows that ongoing spelling instruction based on the sounds of language is effective and produces good results. Students benefit from direct, systematic instruction that moves them along a continuum from the easiest sound/spelling patterns to the most difficult. Instruction is most effective when words with common features are grouped together in the lessons.

Here is a simple sequence of phonics elements for teaching sound-out words that moves from the easiest sound/spelling patterns to the most difficult:

- Consonants & short vowel sounds

- Consonant blends & digraphs

- Long vowel/final e

- Long vowel digraphs

- Other vowel patterns

- Syllable patterns

- Affixes

Teaching Spelling of High-Frequency Words

Eight words account for 18% of all the words students use in their writing, 25 words account for 33%, 100 words for 50%, 300 words for 65%, 1000 words for 86%, 2,000 words for 95%, and 3,000 words for 97% (Fry, Fountoukidis, & Kress, 2000; Horn, 1926; Otto & McMenemy; 1966, Rinsland, 1945). It is smart to make these words a high priority in spelling instruction.

To require a student to master a spelling vocabulary significantly larger than 3,000 words is out of harmony with research. After several hundred words have been learned, the law of diminishing returns begins to operate (Allred, 1977). So, if students master about 3,000 words, they have about 97% of the words they will need.

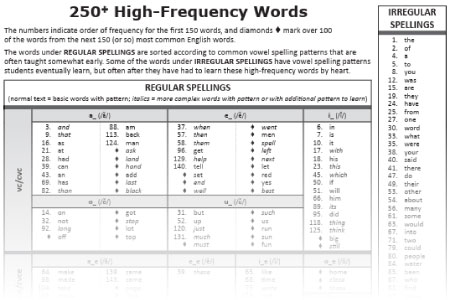

The following list includes 250+ high-frequency words.

The following list includes 250+ high-frequency words.

Spelling List: 250+ High Frequency Words

Spelling List: 250+ High Frequency Words

The column on the left-hand side lists the high-frequency words that have irregular spelling patterns in their order of frequency. The other columns list high-frequency words with regular spelling patterns, organized by common vowel spellings. Use this list to remember to emphasize the high-frequency words with regular spelling patterns as you teach the various vowel patterns.

Learning Irregular High-Frequency Words

Irregular high frequency words should be taught as spell-out words—teaching them in the order of their frequency. Spell-out words should be taught using word-specific memory—say the word, spell the word, say the word again.

When a student studies words with irregular spelling patterns independently, the student should practice a word by saying the word, saying and writing each letter, and then saying the word again. The student should then check the spelling against a correct model and practice again—as many times as necessary.

Learning Regular High-Frequency Words

High frequency words with regular spelling patterns should be taught as sound-out words in lessons with the same patterns. Sound-out words should be taught by listening for each sound in a word and then writing the letter (or letters) that correspond to each sound.

Since some high frequency words have regular spelling patterns that are taught much later in a spelling program, those words should be taught as spell-out words earlier and then reviewed as sound-out words when their spelling pattern is taught later.

Teaching Spelling of Frequently Misspelled Words

A small number of words—about 300—account for more than half the words students misspell in their writing. A Research in Action project reviewed 18,599 written compositions of children in grades 1–8 (Cramer and Cipielewski, 1995). The researchers noted spelling errors in these compositions and compiled the results. They found that a small set of common words tend to be misspelled over and over. These words are misspelled by students at primary, intermediate, and middle school levels.

The researchers compiled this list of commonly misspelled words:

Spelling List: The 100 Most Frequently Misspelled Words Across Eight Grade Levels

Spelling List: The 100 Most Frequently Misspelled Words Across Eight Grade Levels

If you look down this list you will notice these recurring spelling problems:

- Homophones: Homophones—words that sound the same but are spelled differently—constitute about 20 percent of the misspelled words (e.g., there spelled their).

- Apostrophes: Words that contain an apostrophe make up about 10 percent of the misspelled words, some of which are also homophones (e.g., you’re spelled your, it’s spelled its).

- Separation/Joining Errors: Another highly predictable spelling problem involves words that lend themselves to inappropriate separation or joining (e.g., because spelled be cause, a lot spelled alot).

- Errors in Compound Words: Another common spelling problem is the misspelling of compound words by wrongly separating them, or less commonly, by wrongly joining an open compound or joining a compound with a hyphen (e.g., outside spelled out side, ice cream spelled icecream, baby-sit spelled babysit, etc.).

Words that primary grade students misspell are in many instances the same words intermediate and middle school students continue to misspell. When researchers closely examined the 25 most frequently misspelled words at each grade level they noted a startling amount of overlap across grade levels from one through eight.

At the same time, an examination of a typical spelling curriculum shows that many of these frequently misspelled words are taught fairly early in the spelling curriculum. Unfortunately, many of these words are taught only once within the span of an eight-year spelling curriculum.

Teaching these words one time in a spelling series that covers six or eight grade levels is not adequate for many students to learn these words. Teachers should implement a system for reviewing and recycling these words until students demonstrate mastery. Students should be monitored and held accountable for correctly spelling these words in their daily work. Words that continue to be misspelled should be recycled into the next spelling lesson.

Using the Test-Study-Test Technique to Teach Spelling

Evidence from research shows that the test-study-test technique is the single most effective strategy in spelling instruction. This involves having the student (under the teacher’s direction) correct his or her own errors immediately after taking a spelling pretest.

Following each word or at the end of the pretest, the teacher spells each word, emphasizing each letter as the student points to each letter being pronounced. Using a colored pencil, the student puts a dot under the incorrect part of a word and then writes the word correctly off to the side.

The test-study-test method allows the student to:

- See which words are difficult,

- Locate the part of the word that is troublesome, and

- Correct errors.

The student can then focus on the difficult parts of specific words when studying for the final test (Allred, 1977; Darch et al., 2000; Hall, 1964; Hibler, 1957; Morton, Heward, & Alber, 1998).

Read Naturally Programs for Teaching Spelling or That Support Spelling

Teaching Spelling With Signs for Sounds

Read Naturally’s Signs for Sounds is a research-based spelling program for beginning and developing spellers and readers. Signs for Sounds provides systematic, explicit phonics instruction to teach students how to spell words with regular spelling patterns (sound-out words) and a systematic strategy for teaching students how to learn to spell high frequency words with irregular spelling patterns (spell-out words). In addition, the flexible lesson design prompts teachers to recycle frequently misspelled words from week to week until those difficult words are mastered.

Read Naturally’s Signs for Sounds is a research-based spelling program for beginning and developing spellers and readers. Signs for Sounds provides systematic, explicit phonics instruction to teach students how to spell words with regular spelling patterns (sound-out words) and a systematic strategy for teaching students how to learn to spell high frequency words with irregular spelling patterns (spell-out words). In addition, the flexible lesson design prompts teachers to recycle frequently misspelled words from week to week until those difficult words are mastered.

Learn more about how Signs for Sounds uses research-based strategies to teach spelling:

Other Programs That Support Spelling

The following programs do not focus on spelling but include spelling activities as part of a broader scope of instruction:

| Read Naturally® GATE Teacher-led instruction for small groups of early readers. Focuses on phonics, high-frequency words, and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary. A spelling step provides students with practice writing short words with the featured sounds.  Learn more about Read Naturally GATE Learn more about Read Naturally GATE Read Naturally GATE samples Read Naturally GATE samples |

| Word Warm-ups® A mostly independent program with audio support on CDs that develops automaticity in phonics and decoding. Focuses on phonics with additional support for phonemic awareness and fluency. In an optional spelling activity, the teacher (or software) dictates words with the featured pattern and the student spells them.  Learn more about Word Warm-ups (reproducible masters with audio) Learn more about Word Warm-ups (reproducible masters with audio) Learn more about Word Warm-ups Live (web application) Learn more about Word Warm-ups Live (web application) Word Warm-ups samples Word Warm-ups samples |

Bibliography

Allred, R. (1977). Spelling: The application of research findings. Washington DC: National Education Association.

Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K., Abbott, R. D., Brooks, A., Begay, K., Curtin, G., Byrd, K., & Graham, S. (2000). Language-based spelling instruction: Teaching children to make multiple connections between spoken and written words. Learning Disability Quarterly, 23(2), 117–135.

Cramer, R. & Cipielewski, J. (1995). Research in action: A study of spelling errors in 18,599 written compositions of children in grades 1-8. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

Darch, C., Kim, S., Johnson, S., & James, H. (2000). The strategic spelling skills of students with learning disabilities: The results of two studies. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 27(1), 15–27.

Ehri, L. (2000). Learning to read and learning to spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorders, 20(3), 19-49.

Fitzgerald, J. (1951). The teaching of spelling. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company.

Fry, E. B., Fountoukidis, D. L., & Kress, J. E. (2000). The Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists, 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Graham, S. (1999). Handwriting and spelling instruction for students with learning disabilities: A review. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22(2), 78–98.

Hall, N. (1964). The letter marked-out corrected test. Journal of Educational Research, pp. 58, 148-157.

Hanna, P. R., Hanna, J. S., Hodges, R. E., & Rudorf, E. H., Jr. (1966). Phoneme-grapheme correspondences as cues to spelling improvement. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Hibler, G. (1957). The test-study versus the study-test method of teaching spelling in grade two: Study 1. Unpublished masters thesis, University of Texas.

Horn, E. (1926). A basic vocabulary of 10,000 words most commonly used in writing. Iowa City: University of Iowa.

Horn, T., & Otto, H. (1954). Spelling instruction: A curriculum-wide approach. Austin: University of Texas.

Mehta, P. D., Foorman, B. R., Branum-Martin, L., & Taylor, W. P. (2005). Literacy as a unidimensional construct: Validation, sources of influence and implications in a longitudinal study in grades 1–4. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 85–116.

Monson, J. (1975). Is spelling spelled rut, routine, or revitalized? Elementary English, 52, 223-224.

Montgomery, D. J., Karlan, G. R., and Coutinho, M. (2001). The effectiveness of word processor spell checker programs to produce target words for misspellings generated by students with learning disabilities, Journal of Special Education Technology, 16(2).

Morton, W. L., Heward, W. L., & Alber, S. R. (1998). When to self-correct?: A comparison of two procedures on spelling performance. Journal of Behavioral Education, 8(3), 321–335.

National Commission on Writing for America’s Families, Schools, and Colleges. (2005). Writing: A Powerful Message from State Government. New York: College Board.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769), Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 13–14.

Otto, W., & McMenemy, R. (1966). Corrective and remedial teaching. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Rinsland, H. (1945). A basic vocabulary of elementary school children. New York: Macmillan.

Singer, B., and Bashir, A. (2004). Developmental variations in writing. In Stone, C.A., Silliman, E. R., Ehren, B. J., and Apel, K. (eds.), Handbook of language and literacy: Development and disorders, pp. 559-582. New York: Guilford.

Snow, C. E., Griffin, P., and Burns, M. S. (eds.) (2005). Knowledge to Support the Teaching of Reading: Preparing Teachers for a Changing World. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Swanson, H. L., Hoskyn, M., & Lee, C. (1999). Interventions for students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of treatment outcomes. New York: Guilford Press.

Essential Components of Reading

Read Live Accelerates All Students' Reading Success

(~3 minutes)

Read Live uses the science of reading to deliver measurable results for struggling and developing readers of all ages by combining four highly effective instructional programs under one easy-to-use platform.

Read Naturally Live

Improve fluency and phonics skills while supporting vocabulary and comprehension development.

Word Warm-ups Live

Build mastery and automaticity in phonics and decoding with systematic phonics instruction.

One Minute Reader Live

Transform independent reading time into an exciting guided reading experience.

Read Naturally Live—Español

Help multilingual readers develop Spanish literacy skills and fluency.Interested in the research? Download this brief research overview to learn how our evidence-based strategy and programs align with the Science of Reading.

Learn more about how Read Live can help your struggling readers and access a free 60-day trial with a complementary demo.

Please let us know what questions you have so we can assist. For Technical Support, please call us or submit a software support request.